Published time: December 13, 2013 11:01

The dominant theory is currently that this is caused by water eruptions on the surface of the icy moon. But the find is more exciting yet, as it takes us one step closer to observing the possibilities for life there. Because in combination with another study, which found important minerals on the surface, scientists can begin to examine the interaction of minerals above and below the moon’s surface.

In short, all the building blocks for life are there, we just need to get close enough to understand their interaction.

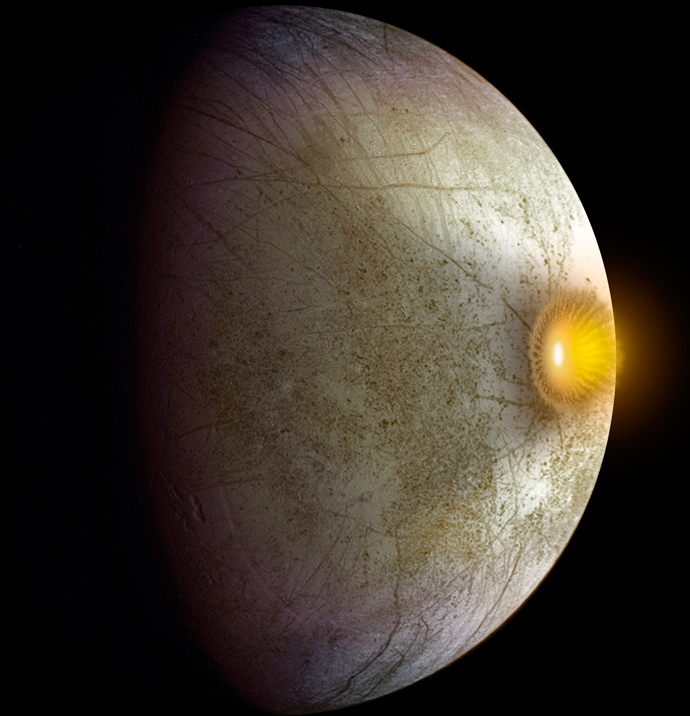

The chemical vapors in the atmosphere, identified by Hubble’s sensitive filters, point to two huge plumes of water occasionally erupting on the South Pole. These eruptions are thought to eject the vapors, which reach such dazzling heights that they are seen from the moon’s orbit. This is a result of being driven by immense tidal forces, which heat up and put pressure on the moon’s vast subsurface oceans. The analysis was published December 12 in the journal Science and on the NASA website, following a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Now, the lead author of the research, Lorenz Roth of Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, believes “If those plumes are connected with the subsurface water ocean we are confident exists under Europa's crust, then this means that future investigations can directly investigate the chemical makeup of Europa's potentially habitable environment without drilling through layers of ice. And that is tremendously exciting."

Because the layer of ice could be tens of kilometers thick, this is a huge breakthrough.

Scientists see the process of chemical interaction on Europa in the following way: the vast subsurface oceans are naturally in contact with the rock below, while the ice that covers them is seen to harbor salts, producing reactions that generate heat – and this is where Jupiter comes in. Its massive gravity pull squeezes and stretches Europa so that its skin cracks and ripples, producing the water vapors and mixing up surface and sub-surface elements.

These are thought to originate from Europa’s past collisions with various space rocks and give further credence to the theory that organic life-forms are indeed very likely on the moon, though no direct evidence has been found yet.

“Organic materials, which are important building blocks for life, are often found in comets and primitive asteroids,” said Jim Shirley of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Finding the rocky residues of this comet crash on Europa’s surface may open up a new chapter in the story of the search for life on Europa.”

The theory describing collision with space rocks is explained by materials ejected from Europa at the time of impact, JPL scientists explain. The collisions probably took place at 45-degree angles, just askew enough for some of the asteroid’s minerals to stay on the surface, instead of being driven underwater.

It is still not known how the phyllosilicates from the moon’s interior could also end up on the surface – since Europa’s icy crust is about 100km thick in certain areas; however that is all the more reason to study those hard-to-reach areas and the complex chemical processes going on inside them.

At this point, scientists are still analyzing whether the massive water vapors are a direct result of the water plumes erupting on the surface, but that is so far the dominant hypothesis.

No comments:

Post a Comment